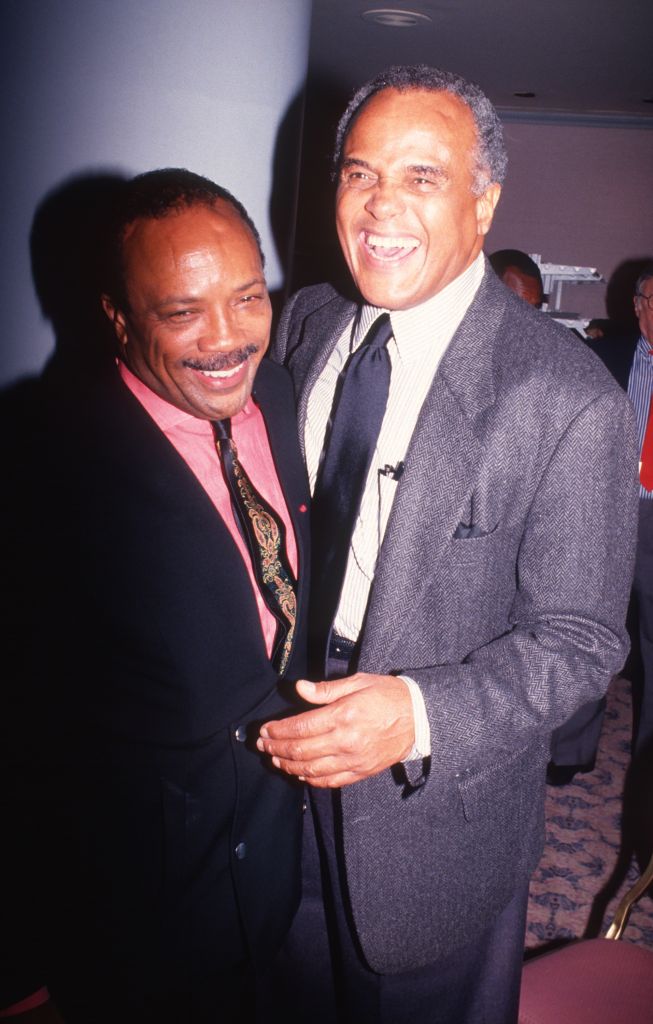

Source: Arnold Turner / Getty

Quincy Jones. Quincy Jones.

Born in Chicago, the City of Big Shoulders, on the South Side, he was the grandson of a woman who’d been enslaved on a plantation in Louisville, Kentucky. She, like the land she walked, the land she worked, was consigned to be forever the property of the Welsh man who was also her rapist.

Despite that origin story, when she gave birth to her son, she named Quincy Delight Jones. My God. The soul of a woman who births her rapist son and names him Delight. All children should know and be able to drink from those life-sustaining waters. It was a good name. A name worn with the love she must have never once stopped pouring into him,

He would pass it on to his firstborn, a baby boy who entered the world on a wide, bright Tuesday, 91 years ago: March 14, 1933. Another Delight. It was a name that suited father and son well. Daddy was a semi-pro baseball player whose trade was carpentry. Somehow, learning that felt less like hearing a Holy metaphor than hearing a Holy truth.

In turn, his boy gave the world a Holiness in his art and vision that will occupy hearts into the next millennia.

In the coming hours and days, others far more qualified than I will detail the exquisite contours of the majestic career of Quincy Jones. They will surely better walk people through the artistry so stunningly powerful and prolific that you wonder if one music historian’s lifetime could possibly be enough to achieve full understanding of an artist operating at his level of vibration. A man who was never supposed to see 40 years on this planet.

That was in 1974. Following a series of strokes, Quincy was told to prepare his papers. As his death drew imminent, he organized his own memorial service, which apparently sent the Grim Reaper scrambling for cover. He didn’t have the courage to come back around until yesterday, Nov. 3, 2024. Quincy Delight Jones drew his last breath at age 91, surrounded by a loving family.

Source: Ron Galella, Ltd. / Getty

The World He Gave Us

I will share just one of the reasons tears gathered in my eyes at just about 3 a.m. on the East Coast. Quincy Jones helped give me a world in which I could find place.

None of the criticism that surrounded “We Are the World” when it premiered in March of ’85 landed on baby teenager me. I don’t think I even knew it was out there until sometime in the 2000s.

In any event, it didn’t stop the recording from selling 20 million copies.It didn’t stop it from being certified quadruple platinum. It didn’t stop it from winning Grammy, AMA or People’s Choice Awards. It didn’t stop production of Netflix’s widely praised documentary of how it all went down back in the winter of ’85. And it didn’t stop this truth: when Quincy drew his final breath on Sunday, Nov. 3, it was still the 8th best-selling single in history.

The Gathering

“We Are the World was written by Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson, and produced and orchestrated by Jones. They first called together what seemed like popular music’s entire royal family: Jackson and Richie, of course, but also Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Paul Simon, Tina Turner, Kenny Rogers, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Dionne Warwick, Cyndi Lauper, Ray Charles and more than 30 other treasured artists.

And then those artists gathered us, the kids stretching so hard to reach even young adulthood, not knowing how fast we’d want back the time we took for granted.

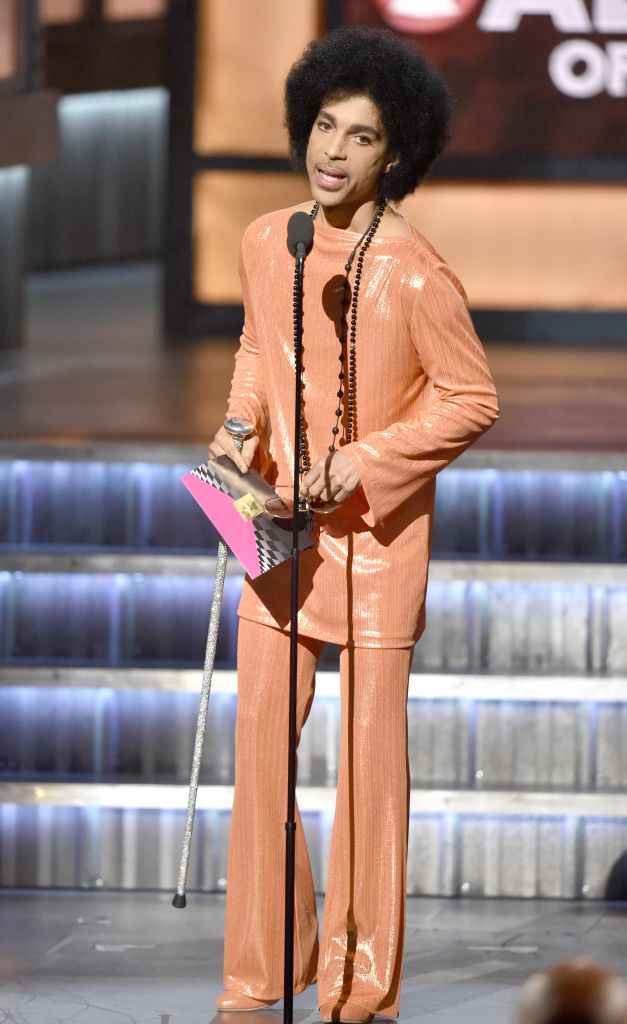

Source: Kevin Winter / Getty

The one stark absence among the artists was The Artist. Prince (predictably?) just didn’t show up for the shoot and recording that began in secret after 11 p.m. in LA the third week of that new year. But the show went on, and the record found an international audience so receptive that by summer, it became a multinational, simultaneously performed, live event on July 13, 1985.

“We Are the World” concert tickets were the ticket to have. Some of my generation–names withheld to protect the reckless–even lied to their parents and slept outside on the streets in front of JFK stadium to get good seating at the ticketed but open-seating event.

And no plot twist here: Harry Belafonte was the one who approached Jones about the war-created famine in the Horn of Africa. He apparently told Quincy they needed to do something to support the people of Ethiopia. They were dying, and photojournalists were leaving painfully malnourished children to perish in the road, flies circling above. Vultures too.

In some ways, for my friends and I, it landed as the genocide in Gaza has on my daughter’s generation: shocking, untenable, and an absolute call to action.

Before we had style, before we had pagers

We didn’t have social media in the 80s. We barely had cable. In my own home, my parents didn’t even have color TV–not that we were allowed to even watch TV. But we had music, 12-inch recordings, and we had artists who were celebrities because of their artistic, not bedroom or surgical adventurism, talent

Their coming together when Quincy created that We Are the World year helped shape my entire life—from writing and organizing to parenting and loving. At the heart of me is a woman who was once a girl who committed fully to doing her best to help ensure human rights, to never turn away from suffering and injustice, to do what I could to end it.

I’ve done my best to honor that girl, although admittedly, sometimes my best actually was pretty bad. But I always returned to the vision: let all of us live endowed with the physical, spiritual and emotional resources that should is every human being’s birthright.

In 1993, Quincy Jones, in partnership with Time, Inc., reached out to the generation whose attention he’d peaked the summer of ’85 by founding and creating Vibe magazine. It became a bible for nearly a full generation of those who claimed proud citizenship in what was called the Hip-Hop Nation.

Quincy tapped Keith Clinkscales, a young Black man not even 30, to serve as its founding president and CEO. No Black person had held such a position at the venerable publisher before. He trusted the one who had no real record of accomplishment in publishing but the FAMU brother who loved Black people enough to make a product that had the world love us too, if only for a moment.

This morning, Clinkscales shared quietly that, more than anything, he felt gratitude for his early mentor, a man whom he loved. Even still, he committed to not mourning but celebrating he majesty of that man’s life.

“How often do we get to see a Black man–any Black man–in America live to see 80, let alone 90? How often do we get to see them be able to use their entire lives to make our entire lives better? We saw that with Quincy. He showed us the possibility of a destiny we’d been told was unreachable for us. He was blessed by God,” Keith said. And that Quincy accepted that blessing so he could give it right back to each one of us.

Let us all tip our hats to the man whose middle name was Delight. Better yet, raise our fists and keep them high in the air.

Let us say thank you, Quincy Jones. Let us say Bravo, Maestro, Bravo. And well done, Brother. So well done.

SEE ALSO:

The Godfather Of Black Music: 15 Ways Clarence Avant Influenced The Music Industry

Quincy Jones’ Gospel Music Legacy

57 photos